Countering Disinformation with the Sentinel Project

Words by Matt Stempeck • Dec 12 2022

One of Code for All’s newest member organizations, the Sentinel Project, is based in Toronto, Canada but works globally. They were founded in 2008 to assist communities threatened by mass atrocities worldwide through direct cooperation with the people in harm’s way and the innovative use of technology. You can learn more in their introduction blog!

These interviews were conducted in mid-2022. Please note that the information might change as the organization seems appropriate.

Meet the Sentinel Project!

Christopher Tuckwood is the Executive Director of The Sentinel Project. I got to speak with Chris the day after their new report dropped: Globally Scaling Digital Solutions for Managing Misinformation. The report emphasizes the need for cross-sector collaboration to tackle disinformation. Given that the goal of Code for All’s research into disinformation is to consider what civic tech groups, specifically, can contribute to the fight, we jumped right in.

Civil society’s strength is that it’s closest to affected communities

“Aside from the technology part of [civic technology], just the civic part, I think, is pretty important,” Chris says. “Although there is a role for government in this, and obviously platforms have a pretty significant role to play as well, arguably civil society is critical because ultimately they’re the people and organizations who are most familiar with the groups that are most vulnerable to these kinds of issues, and also probably have some sense of the best ways to address these issues, especially when it comes to looking at contexts outside of North America and Europe.”

Chris views the civic technology conversation as an extension of civil society groups developing appropriate tools that can support civil society work. The Sentinel Project’s report addresses scaling up local-level initiatives to counter misinformation. I was heartened to see that they found that it is possible and that efforts can be replicated in different contexts while still incorporating varying factors.

The Sentinel Project’s report and its citation of related Johns Hopkins research present some of the many roles civil society can play in countering misinformation:

- Influencing private sector technology policy.

- Advocating for government intervention.

- Providing media literacy education.

- Acting as a watchdog to police social media and expose disinfo campaigns as they emerge.

- Inoculating the public against by supporting education outreach.

- Pressuring tech companies, businesses, and advertisers “that wittingly or unwittingly host, support, or incentivize creators of false and misleading content.”

- “Working with governments, the media, and each other to improve the conditions of mistrust and polarization that create fertile breeding grounds for the spread of disinformation.”

Scaling and replicating successful projects

“Generally speaking, in our experience, we’ve seen that a lot of misinformation management projects around the world tend to take broadly similar approaches. There are basic models and principles that can be replicated and done at a larger scale, with those relevant adjustments.”

Disinformation is a chronic societal issue that will require sustained funding

So what’s missing? Consistent funding. Chris argues that what needs to change is a matter of funders’ mindsets. To date, he characterizes the funding of this work as being guided, too often, by “very short-term thinking and also small-scale thinking, maybe what you might call kind of like solutionism or an expectation that there’s some kind of one-off approach that’s going to solve this problem, once and forever.”

Rather than count on long-shot theses that a single app or policy or single-year grant will fix misinformation forever, we need to adapt our approach to disinformation to match other chronic challenges. “We don’t approach any other kind of development or social issues in the same way,” Chris says. “Nobody ever says, ’We’re going to invest really heavily in education in this one country for one year or maybe two years. And then everybody will be educated and then we’ll never fund education again.’” The same goes for partially funding law enforcement and expecting crime to disappear “Literally nothing else works that way,” Chris says. “It’s more about setting up systems that are going to last.

Funders also unfairly expect disinfo projects to become profitable or self-sustaining somehow, Chris feels, where again, it’s self-evident that in other domains like education, this approach is unlikely to work. Chris argues we could instead treat misinformation management more like a public service that requires ongoing investment. In principle, he believes that scalability and replication of disinfo projects are possible but it’s a question of the resources that are made available and for how long they’re available.

Rumors, misinformation and disinformation, and propaganda have been around for a very long time, in some cases, since time immemorial, basically. So we must adapt our approach to recognize that they’re recurring issues, much like crime. We work to manage and reduce the harms it causes using annualized resources, rather than assume we can completely eliminate it with a prohibition approach.

Capturing and distributing best practices

Like almost every practitioner I spoke to, Chris doesn’t often find the time to review the academic literature on this subject. My assumption is that a combination of a slow turnaround in publishing timelines plus high barriers to entry with paywalls and unclear writing prevent many of the groups fighting disinformation from seeing the benefits. Their time is better spent keeping up with the rapidly evolving tactics and strategies they need to be effective in their work.

Chris wishes he had time to do more writing, even in terms of blog posts, to reflect and share what has worked, what hasn’t, what his team has learned, and future directions but they don’t have the capacity for this because of resource constraints. Chris imagines that other groups find themselves in a similar scenario, where they’ve learned through their efforts what’s working and what’s not, but resource constraints prevent them from developing those findings into formal resources for others to use.

Matching a disinfo taxonomy to proven interventions

Chris dreams about creating a rigorously-curated directory that includes the different types of misinformation, specific examples of it from all around the world, the particular harms they’ve contributed to, and, as applicable, the types of interventions that have been effective at addressing them.

The Sentinel Project designed its own WikiRumours database as a working tool that enables geographically distributed teams to collaborate on the misinformation management process. And there are a variety of other efforts to track and archive both global misinformation campaigns and interventions.

Tracking and archiving disinformation at a global scale, there are efforts like Jigsaw’s map of the Atlantic Council DFRLab’s research into “the methods, targets, and origins of select coordinated disinformation campaigns throughout the world” (with data through 2019).

And tracking and categorizing efforts to fight disinformation, there are resources like the Civic Tech Field Guide’s Fight Disinformation section, which contains over 440 tech tools, media literacy programs, and fact-checking groups.

But what Chris imagines is a reference resource that would link the two sides. It would include a broad typology of rumors and misinformation, and relevant management approaches that have proven efficacious in that context. For example, even before COVID, vaccination campaigns almost always set off rumors and misinformation about the vaccine in question. Similar rumor patterns trail the distribution of humanitarian aid supplies, sometimes resulting in actual attacks on humanitarian workers and facilities. Knowing that these themes recur all over the world, and the specific harms they contribute to, what, if anything, do we know about successfully addressing them that might be replicable in other contexts?

What works and what doesn’t

One of the core principles of The Sentinel Project’s work on misinformation management is responsiveness. Chris says this means having a two-way flow of information with the communities they’re serving. They emphasize a crowdsourcing approach to sourcing misinformation and focus their verification and counter-messaging resources in response to the rumors that people report to them.

This approach allows The Sentinel Project to fill in information gaps based on people’s own self-assessed information needs. Contrast it with the typical publication approach, where a team of editors somewhere decides what the public needs to hear about. This model assumes that the public will remain a passive actor.

Too many similar crowdsourced disinformation projects, Chris says, “tend to be almost purely extractive in terms of getting data from populations. They don’t report back to the people who are reporting them to them either on an individual or collective basis.” When projects expect communities to report things for the sake of reporting, without acknowledgment or gratitude, it can “feel like you’re sending information to a black hole for no apparent reason,” Chris says. “We need to return practical value to people in terms of telling them whether or not information is actually true. It would be like if you called 911 and they just recorded your emergency report without sending any assistance. Why would anyone ever call them again?”

My conversation with Chris helped me realize that there are far more misinformation management projects working on media monitoring and verification than actual counter-messaging. Organizations will collect data, parse it, map it, and put it on a website, but to what end? Too many projects “don’t close the loop and proactively try to disseminate information,” Chris says, so “you can kind of ask yourself, not just from the beneficiary perspective, but just overall, what is the point?”

“And that’s as far as it goes,” Chris continues. “And in a lot of the contexts where we’re working, the vast majority of people are not really looking at any websites, let alone some sort of obscure fact-checking website.”

In my analysis of over 500 misinformation interventions, the vast majority focus on monitoring media and social media or fact-checking and verification. Only a relative few get as far as effectively disseminating accurate information and counter-messaging.

Chris theorizes that this paucity of “last-mile” interventions comes down to the fact that managing misinformation is often a sequential, three-step process: monitoring, verification, and response. The response, Chris says, is the hardest part, particularly if organization staff aren’t local to the project and are ensconced in comfortable offices doing the (relatively) easy monitoring and data analysis. “Maybe there’s a bit of an academic mindset that comes from that as well, which is, if we just gather and analyze data somehow that in and of itself is going to help, which you know, may be helpful from a learning and knowledge-generation perspective, but from an impact perspective it has fairly little value,” Chris says.

Graphic from The Sentinel Project’s report, Globally Scaling Digital Solutions for Managing Misinformation (pp. 11), which illustrates the sequential order of Monitoring, Verification, and Counter-messaging phases of the organization’s work.

The most impactful stage of the work, responding to misinformation within communities, doesn’t necessarily appeal, in The Sentinel Project’s experience, to the types of people and organizations who are doing a lot of the disinfo work. It’s also possible that fact-checking and media efforts introduce artifacts from the traditional publishing model, “where you do your research and publish it, and then you’re done with it,” Chris says.

For the past twenty years, the engagement journalism community has worked to create genuine feedback loops with newsrooms, where publishers care about two-way conversations with the people their stories cover and affect. But the default model for the media is still to publish information in a one-way approach and bemoan the low-quality discussions in the comments section, if not disable them entirely. I’ve long been a fan of solutions journalism for exactly this reason, as it encourages journalists to go a step further in their reporting and connect audiences to action on the subject of their stories.

Chris concurs and says that publishing is a very different model but he believes that fact-checking claims, and putting them on a website isn’t good enough: “You can’t just stick it on a website and feel like that has somehow addressed the problem.” The problem with this approach, Chris says, is that it doesn’t take into account:

(1) accessibility in terms of whether people in a given context can actually access a website

(2) whether they actually know about the website’s existence

(3) whether they would want to access it, even if they could since it might not fit into their preferred way of accessing information.

These approaches to disinformation work create a profound disconnect between the information landscape of the affected populations and many of the projects meant to benefit them.

Language

The principle of responsiveness manifests in other ways, too. The most obvious example, yet still a common one, is when organizations don’t even bother to translate their work into the languages used by the intended beneficiaries, much less culturally localize the program. “It’s wild, really, how little consideration there is for the audience,” Chris says. He gives an example of a project intended to benefit Ukranians that wasn’t translated into their language, or other languages many Ukranians speak.

Strong linguistic representation is an important priority for The Sentinel Project’s work on disinfo and local partners or staff (depending on the project) are often critical for achieving it. “Having local people who understand not just the context but the relevant languages is really important.”

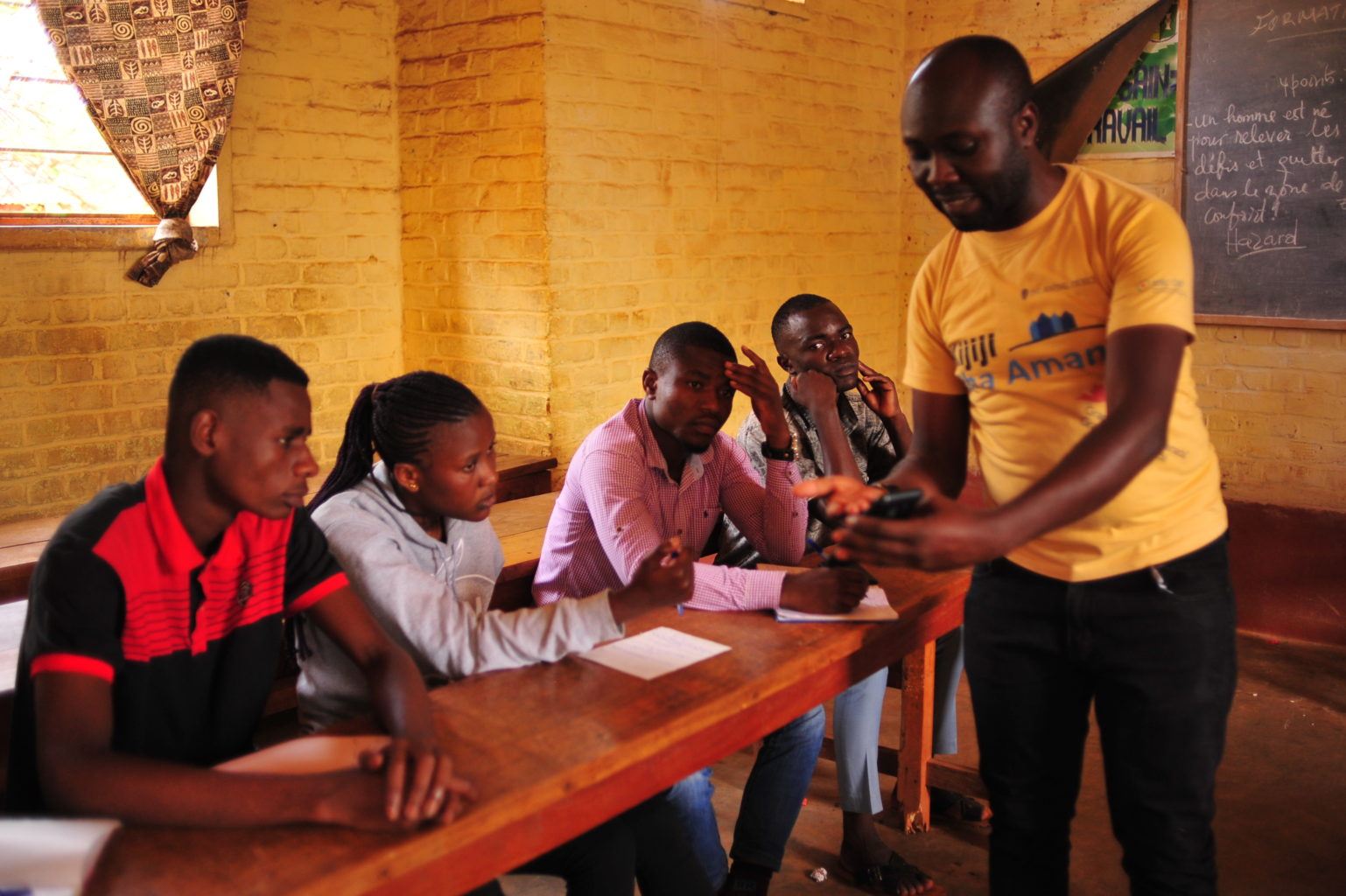

Beyond paid staff and colleagues at partner organizations, The Sentinel Project recruits a network of trained volunteers to serve as community ambassadors. They are the human face of the project and its eyes and ears within their communities. Chris credits this model with helping them reach more local languages. He also points out that literacy is another issue related to language; people in a community might be fluent in one language but only literate in another. This is a critical consideration for ambassadors’ face-to-face conversations as well as technical systems that rely on users inputting text, such as via SMS.

The community ambassadors also help lower the technical barriers to participation. As community members themselves, the ambassadors can act as proxies for people regardless of their technological comfort. Combined, these approaches help The Sentinel Project keep abreast of the rapidly evolving lexicon of misinformation.

Needs

- Like every group, funding is the biggest priority for The Sentinel Project’s work. The resource constraints and unpredictability of funding limit their ability to scale successful programs.

- Connections to other organizations doing similar work, whether thematically similar or working in some of the same countries, or developing useful tools. The Sentinel Project’s capacity for developing unfunded partnerships and collaborations is limited but even just the ability to exchange knowledge with peer groups is often valuable.

- Related to funding, Chris points to the importance of sustained funder interest in the places where people need the most help. Funding trends dictate where, geographically, the organization can afford to operate. The trends shift every few years, and often ignore places where people really need help, Chris says:

“As an organization that is aiming to do atrocity prevention and mitigation regardless of whether that means dealing with misinformation or some other approach, the ideal way of working would be to have our assessment criteria, look at which countries are most in need, and then ask what are the drivers of risk there? And what are the approaches that can help to reduce that risk? And then actually going and implementing that.”

Instead, the organization has to balance a limited budget with the reality of where in the world funding is readily available to do the work. Chris brings up Kenya, where The Sentinel Project worked ahead of this year’s election. Kenya is generally neither the highest-risk country nor the hardest to fundraise to do work in. Compare Kenya to other contexts, like Democratic Republic of the Congo, where funding is much, much harder to land, despite the needs of the people in those places. The Sentinel Project does run a project in Congo “but funders seem to have just forgotten about [the country],” Chris says. “And even worse is somewhere like the Central African Republic, where we tried getting a project off the ground but there was just no international attention on CAR. It’s just not a priority country for funders.” This dynamic forces The Sentinel Project to constantly evaluate its options, asking “Where do we actually see the need for this work and want to do this work? And then is there actually money available for it?”

Constantly shifting funder attention harms civil society’s ability to do consistent work in a place that needs help, Chris says. He points to South Sudan, which has been “a bit more on the donor radar” in recent years. “But then, the 2022 invasion of Ukraine happened and suddenly all the attention went there. And it’s not like Ukraine doesn’t deserve attention, but at least for Western countries, which are still the majority of donors, it was suddenly like there was nothing else in the world besides Ukraine, like every other conflict just faded into the background and like nothing else mattered.” He doesn’t want to see Ukraine go through the same thing Myanmar did, where it was the funders’ favorite place to invest for a few years, only for many of them to move on to the next thing. “You can do more than one thing at a time.”

Interested in learning more?

Matt Stempeck, the National Democratic Institute, and Code for All worked on a research project to understand how civic tech can help confront disinformation. The project’s goal is to learn from (and share out!) lessons learned from organizations that focus on this area.

Check out the Disinformation Research Project to learn more and help us spread the word!