Civic Hacking for COVID-19 Recovery: The Story of Code for Korea

Words by Eunsoo Lee and Ohyeon KWEON • Sep 6 2022

Code for Korea is a network of civic hackers committed to citizen-led collective problem-solving. We work on a range of topics, from the most intimate, everyday issues to national and global crises.

In this blog, we wanted to introduce the story of how we came together, as an autonomous group of citizen developers who wanted to make a difference in times of unprecedented public crisis.

Organising a joint response for COVID-19 open data & developing the public masks app

9:00 am on March 11, 2020, marked the launch of the first ‘public masks’ app created jointly by the civic hacker community and the South Korean government. The app informed the public on the availability of face masks, which were quickly running out due to high demand.

Soon, an extensive list of apps (16 mobile apps and 38 web services) was created by over 300 volunteers from the developer community. This all happened two weeks after the ‘COVID-19 Open Data Joint Response’ filed a request to the government for open data release, and one week after the community —together with the government— started developing the public masks app using the ‘public masks inventory’ data. An extraordinary system and service that allowed citizens to check the availability of face masks in real-time (*1 minute delay), with inputs from individual pharmacies, was made possible within a week.

In the early days of COVID-19, many individual developers in Korea released apps that provided timely and accurate information about the pandemic. This included up-to-date statistics, as well as web services that tracked possible sites of transmission. At this point, developers had to manually extract the data from the government’s daily updates, which were released in the form of tables and visualisations. This is what prompted a group of civic hackers to organise a joint response for the release of COVID-19 open data, so that more citizens could be involved in the nationwide pandemic response.

The request by the ‘Joint Response’ team included basic statistics, data around clinics and treatment facilities, and if and when the government decided to distribute COVID supplies, such as face masks and hand sanitizers, that they make this data available as well.

It was around the time of the request that the face mask supply shortage problem surfaced. As cases rose and uncertainty around this novel virus persisted, panic-stricken citizens had started to form long lines in front of pharmacies to purchase the rapidly dwindling reserves of face masks.

As a response, the South Korean government initiated a public-private consultation in which a set of rapid measures —including the proposal by the Joint Response team to disclose government data and use community/private sector-led app development— were accepted as possible solutions. The Joint Response team became actively involved in the data disclosure process and the organising of a development team for the public masks app.

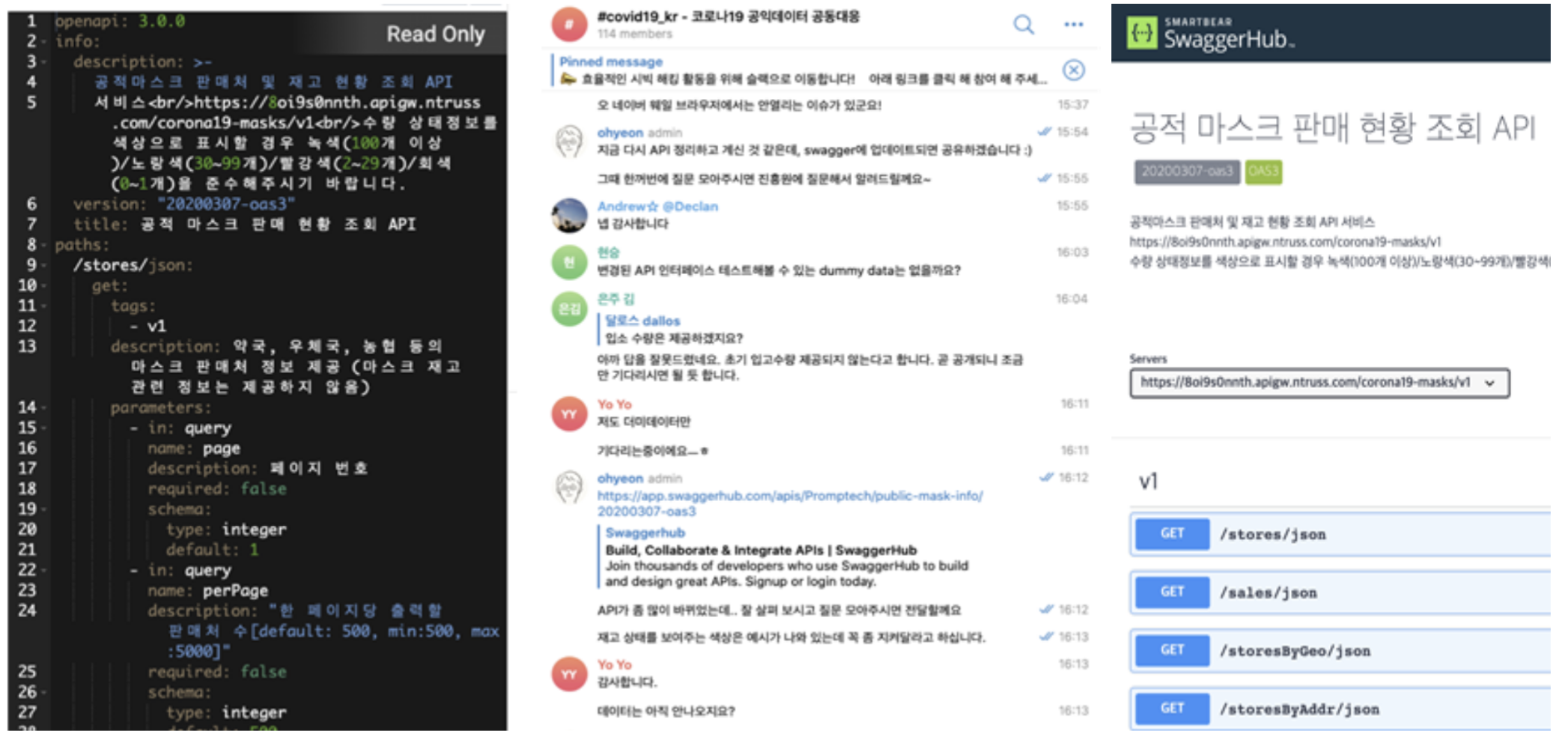

Within days, more than 200 developers came together to validate and improve the API-in-development, and started to create numerous apps based on the mask inventory data. In the process, the team also created documentation to provide guidelines around making use of public data and participating in the project. In four days, the development was almost complete, and the team prepared for a coordinated launch of the service.

To address the face mask shortage problem, the government began distributing a limited number of ‘public provision masks’ (i.e. public masks), which allowed the public to purchase a designated number of masks per person. Soon after the disclosure of government data around public masks was confirmed, on March 11, dozens of ‘public masks apps’ were released at the same time.

On the day of the launch, the apps were accessed more than 90 million times, and from there on were accessed more than 170 million times a day. The sell-through rate of masks rose from 67.9% to 86.4% and people no longer had to queue in front of local pharmacies.

A big takeaway from the public masks app project was witnessing how preemptive measures taken by the government, based on information transparency, helped reduce public anxiety and encouraged public participation in collective problem-solving. This has become an important strategy for the Korean government in their response to COVID-19.

Above all, for those who participated, it was an opportunity to understand the power of civic capacity and the role of the government in facilitating it. Citizens can take part in solving societal problems and the government can provide a space for collaboration.

Through this project, we shared a collective experience of seeing the change in ourselves, our neighbours, and the larger society. We used to share stories about the fact that we finally realised how we as citizens could contribute to society using technology, and how incredible it was for the government to be able to collaborate with citizens in this way.

Beyond COVID-19 response

Since 2010, the Korean civic hacking community slowly began to establish itself on a regional basis. Many did not explicitly identify as ‘civic hackers’, but time after time, citizens emerged in times of crisis, and initiated activities that leveraged technology as a tool for civic intervention.

Meanwhile, the COVID-19 Open Data Joint Response team had grown to a network of 300 developers. The experience of the coordinated response around public masks allowed us to launch a civic hackers network, which we named, “Code for Korea”. Since the initial COVID response, we have been involved in several pandemic-related initiatives.

In early 2021, at the request of the Personal Information Protection Committee, we developed a program that assigns anonymised security numbers (in place of identifiable information such as phone numbers) that could be used by the authorities for contact tracing. Code for Korea led the entire process from proposal to development. This program was actively adopted by major IT/telecom companies such as Kakaotalk, Line, KT, and SKT in their verification apps.

Our work has also diversified beyond COVID, including projects around environmental justice (creating Net Zero Dashboards using open data), inclusive mobility (crowdsourcing and mapping barrier-free facilities), public memory (launching an online memorial for workers who suffered fatal work injuries), and open data activism (requesting the government commits to better data sharing and transparency practices).

Expanding the network and collaborating with institutions – connecting existing civic hacking initiatives

We have already entered an era in which citizens proactively use technology to solve and intervene in various societal problems. Facing an increasingly complex set of crises —ranging from environmental to economic and political —we hope that Code for Korea can serve as a platform to invite diverse members of Korean society to engage in civic-led problem-solving.

Moving forward, and utilising our affiliation with Code for All, we hope to expand our network and open up opportunities for collaboration within and beyond Korea.